After reading many articles, monographs and books as well as attending conferences all on the topic of education, here's what I've learned:

The most important criterion that maximizes student learning is teacher moderation, system leaders attending professional development with their teachers, differentiated instruction, critical thinking, safe schools initiatives, coaching, teacher collaboration, and the list goes on (subject-verb agreement error intended).

Other related research-based evidence seems to indicate that what really makes a lasting impact is student mental health initiatives, connecting with positive adult role models, inquiry, 21st century skills, character education... (again: subject-verb agreement error intended).

From conversations with many excellent teachers, I've learned that what goes around comes around, the pendulum has swung too far the other way, we need more money for books, the system/board/jurisdiction is top heavy and out of touch -- when was the last time they were in a classroom? -- what we really need is more (fill in the blank) and less (fill in the blank).

Many of the above arguments are equally passionate, well-reasoned and researched.

Stakeholders? I could give yet another compelling list of what parents and taxpayers think are the most important factors. When was the last time you heard a rant that starts with, Well when I was a student...?

Speaking of students: yes, let's not forget them. The board I'm part of just held a student voice forum in which we discovered that students want more group work/less group work; more smartboard activities/less smartboard activities; showing movies good/showing movies bad...

Reflecting on this dizzied me until one day I was introduced to a theological model -- quite the leap, I know -- which suggests that the quest for ultimate spiritual truth is not as simple as exclusively examining the holy scriptures. Wars have been waged over the disagreement on how the holy texts inform us about truth. The Wesleyan Quadrilateral suggests that the quest for truth comes from the complex interaction of, yes, primarily scripture, but also tradition, reason and experience.

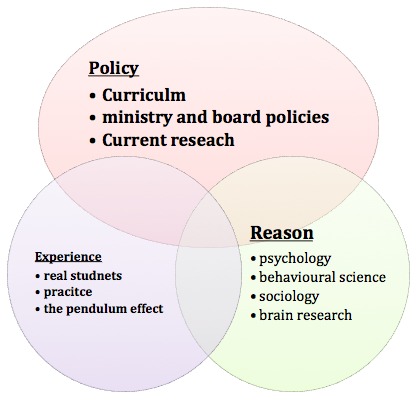

This got me thinking; and my thinking led me to unabashedly rip off the Wesleyan Quadrilateral to create my own model for what I'd like to call Educational Epistemology (fancy for informed practice).

Here's what I'm suggesting: informed practice -- whether we're talking about a board, a school or a classroom -- comes most definitely from starting with current policy, curriculum and research, but also considering educated reason (the science of human behaviour, for example) and experience (real-time, on-the-ground as well as historic practice).

I've come to believe that those of us who are not in the classroom not only run the risk of alienating teachers when we tout the latest and greatest pedagogical thinking, we also often devalue their real concerns; when they tell us that won't work in their classrooms, we should listen very carefully. We should allow it to inform our thinking. On the flip side, I've also come to believe that too often the dismissal of current educational research comes not out of informed conscientious objection but rather out of fear of the unknown and/or -- quite frankly -- laziness. So where does informed practice lie? It lies in the intersection between policy and experience and it happens best when the two camps truly honour and value each other.

The same can be said of educated reason and policy or practice. For example, one of the best books I've read about education is one which is not primarily about education. It is Daniel Pink's Drive. In Drive, Pink argues that people are mostly motivated by intrinsic -- not extrinsic -- factors. Pink dedicates an entire chapter to education which, without going into the details, makes some very relevant points. Having said this, I wouldn't use the entirety of Daniel Pink's Drive as a blueprint to overhaul education. I would, however, strongly consider what his research says about how motivation and change happens; and I would look at Pink's research in light of how our curriculum, policy guidelines and experience inform us. That is, where do the circles intersect?

One of the reasons why I've been contemplating this as much as I have been lately is because next year I will be going back to the classroom. Tonight, I will lead a group of teachers as we examine the importance of student choice is developing secondary school reading programs. We will specifically discuss gender-specific book clubs, literature circles and classroom libraries. I believe that what I will tell them is true. I've even practised some of what I will preach later today. I do, however, have this niggling fear that next year when research meets practice -- my practice -- I'll be eating some of my words. More accurately, I'll be redefining informed practice as it lies in the sweet spot where everything I've learned -- about education and all things closely related -- meets the 80 or so students with whom I will be entrusted. In other words, I would hope that I will not rely solely on policy, on experience or on reason. Rather, I would hope that all three will inform how I practice next year.

I've come to believe that those of us who are not in the classroom not only run the risk of alienating teachers when we tout the latest and greatest pedagogical thinking, we also often devalue their real concerns; when they tell us that won't work in their classrooms, we should listen very carefully. We should allow it to inform our thinking. On the flip side, I've also come to believe that too often the dismissal of current educational research comes not out of informed conscientious objection but rather out of fear of the unknown and/or -- quite frankly -- laziness. So where does informed practice lie? It lies in the intersection between policy and experience and it happens best when the two camps truly honour and value each other.

The same can be said of educated reason and policy or practice. For example, one of the best books I've read about education is one which is not primarily about education. It is Daniel Pink's Drive. In Drive, Pink argues that people are mostly motivated by intrinsic -- not extrinsic -- factors. Pink dedicates an entire chapter to education which, without going into the details, makes some very relevant points. Having said this, I wouldn't use the entirety of Daniel Pink's Drive as a blueprint to overhaul education. I would, however, strongly consider what his research says about how motivation and change happens; and I would look at Pink's research in light of how our curriculum, policy guidelines and experience inform us. That is, where do the circles intersect?

One of the reasons why I've been contemplating this as much as I have been lately is because next year I will be going back to the classroom. Tonight, I will lead a group of teachers as we examine the importance of student choice is developing secondary school reading programs. We will specifically discuss gender-specific book clubs, literature circles and classroom libraries. I believe that what I will tell them is true. I've even practised some of what I will preach later today. I do, however, have this niggling fear that next year when research meets practice -- my practice -- I'll be eating some of my words. More accurately, I'll be redefining informed practice as it lies in the sweet spot where everything I've learned -- about education and all things closely related -- meets the 80 or so students with whom I will be entrusted. In other words, I would hope that I will not rely solely on policy, on experience or on reason. Rather, I would hope that all three will inform how I practice next year.